I've mentioned before that I'm what my company calls a "lead" developer, which means I'm in charge of projects, not people. It is my responsibility to assign work, conduct code reviews, divvy up tasks, etc. It may sound like this position means doing a lot of paperwork (and, in fairness, sometimes it means exactly that) but for the most part I love my job.

That said, leadership is not a quality you are born with, as I can personally attest to. For most of my school days and the first five years of my professional career, I was the opposite of a leader; a loner, content to lurk all day in my ivory tower and only emerge when I'd solved some problem, be it calculus or my essay for English class. I didn't listen to others, I was never wrong, I didn't ask why because I already "knew" the answer. I was the classic nerd, the anti-social, sci-fi loving, helps-all-the-people-with-their-homework-but-never-gets-a-date 80's-movie geek. I'm still that guy to some degree.

Four years ago, I was laid off from a job I didn't particularly like and my whole viewpoint changed irrevocably. I had felt like I had no control in that situation, and I was sick of being only a sidekick in my game of life and not the main player. I needed to do something else, something fulfilling, and I slowly came to realize that for me, being a teacher was what I liked to do. I'd truly enjoyed assisting my classmates with their schoolwork, and now I wanted to help others.

Teacher, information and computer science by Wonderlane, used under license.

Two years ago, an opportunity arose in my organization for a lead developer role, and I quickly volunteered. I had no previous leadership experience, and up until that point becoming anything other than a code monkey hadn't even been a consideration for me. But I saw my opportunity to teach, to guide, to help, and I grabbed it and didn't let go. Finally I had some measure of control back.

Since I haven't been either fired or demoted in the time that I've been a lead, I can conclude that I'm doing an acceptable job. I think. At any rate, while I've found this position largely to my liking, there's been a few things I needed to learn on the way. In my case, four ideals have helped me become a better lead developer and could help out those of you who might wish to be (or already are) a leader of some kind in your organization. I try to keep these ideals in mind every day I'm at my desk.

So what are they? Glad you asked!

Delegation Is Your Friend

There's only one of me (as far as I know), and as such if I ever wanted to have time to do something else I had to consciously try to not do everything myself. After all, what good are having teammates if you never give them anything to do?

Tuesday to-do list by Stacy Spensley, used under license.

When I was promoted to lead, I kept thinking in terms of my time. Oh, I know this project, this will only take a couple hours which promptly fell apart because I was already stretched too thin. Sixteen two-hour tasks that are all due tomorrow are too many balls in the air for one programmer to juggle, no matter how capable they think they are. I was forced to start giving some of my balls away to trusted, capable members of my team...

Are we done giggling now? Good.

As I was saying, we can't do everything by ourselves, so we have to trust others to do some of it for us. Trust is the hard part; it takes a while to be able to trust anyone with something we give them. But once that trust is established, we'll be able to assign tasks and code to our teammates and know that they'll get it done correctly, efficiently, completely.

You can't do it all yourself; delegation is your friend.

Listen Up

Ever woken up in the middle of a conversation and realized that you had no idea what the other person was saying? (If you have: just smile and nod. Eventually they will leave.) This is something we should not ever do when talking with your teammates. They are our eyes and ears into the code that you may not be personally familiar with; you need them to squash bugs and implement features and run tests that you may not be very skilled at doing, or even able to do at all. But if we are to hear what they are telling us, we need to be able to listen to them.

Listen by Ky, used under license.

This is a particularly difficult thing for me because listening requires focus, but practice has slowly improved my ability to concentrate and fully comprehend what others are saying. If someone is talking at me, it is my job to ensure that they are also talking to me; communication is a two-way street. To do this, I follow two guidelines:

- Look at their eyes. This forces me to pay attention to what they are saying.

- Mentally repeat back what they just said. I find that repetition helps me retain knowledge, so forcing me to repeat to myself what the other person just said is invaluable in helping me digest what it means.

This was wildly uncomfortable for a natural introvert like me when I first started, but as I kept at it I slowly got acclimated to actually looking at people and remembering what they were saying. It's still tough to focus during some conversations (particularly when the topic at hand is contentious or difficult to talk about) but I'm getting better. I truly believe that you cannot be a good leader without being a good listener.

Listen to those around you, and pay attention to what they are saying.

Since I see that you are nodding in agreement (I'm glad we see eye-to-eye on this) I'll move right along.

Be Willing to Be Wrong

Pssh. Whatever. I'm never wrong! It's you guys who are wrong, not me!

Modified from angry tiger by Jaqen, used under license

If you know a programmer that acts like this, you have my permission to slap them. Hard. Repeatedly, if necessary.

We must be willing to entertain the idea that we are wrong at all times. If we constantly believe that we could be mistaken, we become more willing to consider other points of view, other ideas. Part of listening and comprehending is the ability to consider someone else's opinion with the same weight as our own. If we're never wrong, can anybody else ever be right?

Here's an example: say you assign a small bug to one of your junior developers. You give them directions about how to reproduce the bug and how to fix it, and send them off on their way. A little while later, they submit their changes for code review, but when you look over their solution you find that they ignored your counsel and squashed the bug a different way. As it turns out, an objectively better way.

Some programmers would be annoyed that the junior didn't heed their advice, and those people make terrible leads. Ingenuity and creativity are to be celebrated, encouraged, and wasting time being upset that some punk didn't take your obviously sublime advice to heart doesn't help us deliver a product; in fact, it does just the opposite, because now you'll waste time trying to persuade the junior that your way is the One True Way TM rather than getting anything done.

Be willing to be wrong, so that you can objectively consider the possibility that others may be right.

Use The Most Powerful Word

There's a fine line to walk, though, since if we got to a lead position it is unlikely we will be wrong all of the time. This is where the most powerful word, the most important question we can ever ask comes in handy. It's so simple that many adults simply forget to use it at all, but five-year-olds use it all the time.

Why?

Why did you choose to do it that way, instead of the way I told you to do it? Why are these requirements part of this sprint? Why does the button need to be on the right instead of centered in the div? Why does our team sit on this floor rather than the other, and why do we not all sit together?

Reporter raising hand at US Army press conference, used under license

The reasoning is simple: questions lead to answers, answers lead to understanding, and understanding is your responsibility as a lead. Our focus needs to be the bigger picture: how all of the individual stories or tasks fit together, how the end user expects the application to work, how the team will get from A to B during the development process. We need to understand the scope of what we are trying to accomplish in order to actually accomplish it.

Before understanding, though, comes questioning. Ask why, early and often, and don't quit until you get some kind of an answer, especially if it's an answer you don't like, because those kinds of answers are gateways to either comprehension (meaning you are wrong) or clarification (meaning the other person is wrong). Don't be arrogant, don't be brash, just be kind but persistent and you'll get an answer.

Question everything!

Why should I listen to you?

Glad you're already asking the important questions.

You shouldn't listen to me! At least, not without trying some of these things for yourself. I'm just some guy on the internet. But I have been a lead developer for two years, I haven't screwed it up yet, and these four things - delegation, listening, willingness to be wrong and asking "why?" - have been instrumental in my constant quest to learn, to understand, to become a better developer. Maybe, hopefully, they'll help you as well.

And if they don't, well, just smile and nod. Often that gets the job done too.

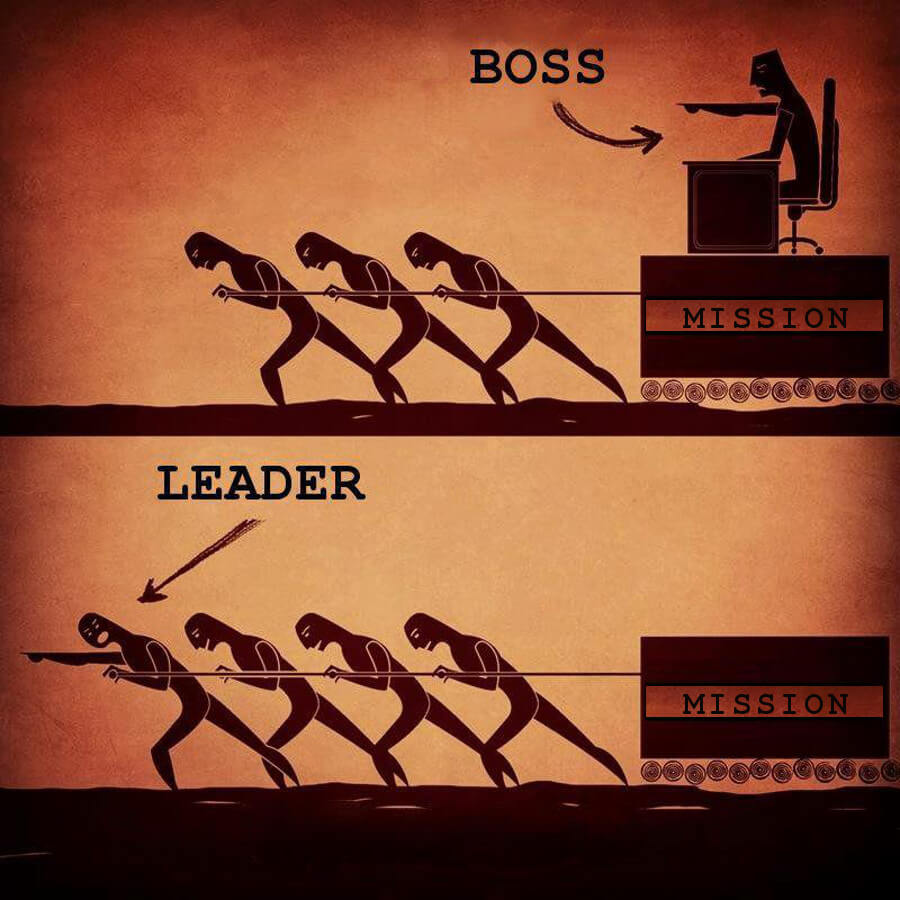

Boss vs leader by John Lester, used under license.